When the System Is Designed to Fail, Rewrite the Code

The phrase “breaking precedent” often conjures images of innovation in boardrooms or startups, not concrete floors and correctional uniforms. But if ever there was a system built on precedent—on routines, assumptions, and rigid structures—it’s our prison system. And no system more urgently demands a rewrite.

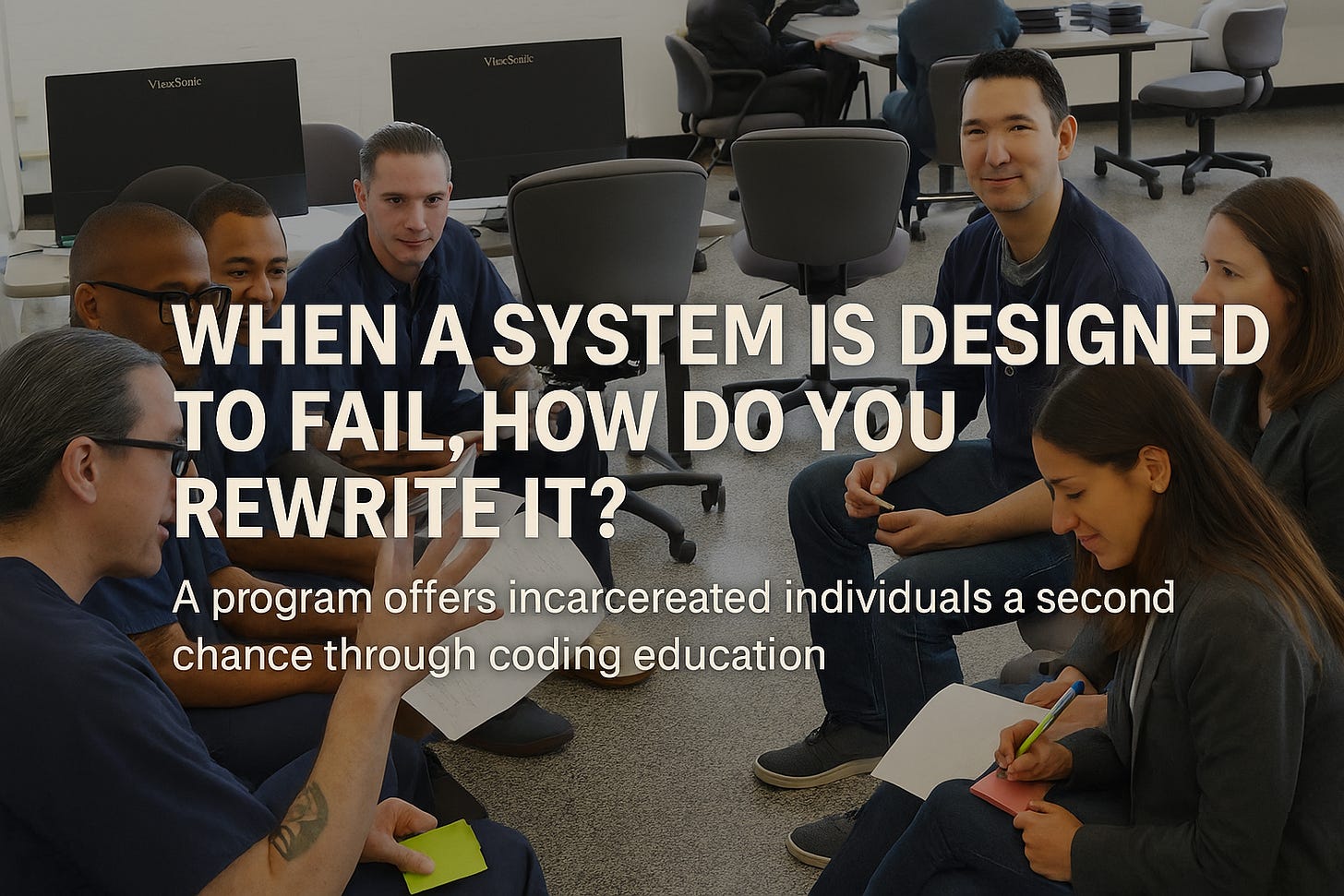

In a recent episode of Breaking Precedent, I sat down with Chris Redlitz and Beverly Parenti, co-founders of The Last Mile, a program teaching coding and entrepreneurship inside prisons. What began as a bold experiment in San Quentin is now a national model, proving that rehabilitation is not only possible—it’s scalable.

Chris said something that stuck with me: “This system wasn’t designed for outcomes. It was designed for containment.”

And once you hear that, you can’t un-hear it. Our incarceration model prioritizes control over opportunity, punishment over progress. It's not failing—it’s working exactly as designed. That’s the real problem.

But The Last Mile offers a counter-design. It gives people in prison the tools of builders—literally. HTML, CSS, JavaScript. They’re learning to debug systems and ship clean code, often for the first time in their lives. These are not just technical skills. They are acts of agency.

One of the most powerful moments in our conversation came when Beverly shared that some participants have declined early release to stay in the program. Read that again. In a place where time is everything, these individuals are choosing to remain incarcerated longer—not out of fear, but because they’re invested in rewriting their own futures. That’s how much this program means.

Consider Billie Edison, a mother of seven who made the extraordinary decision to stay in prison an additional year to complete The Last Mile's coding program. Facing a potential 65-year sentence, Billie found hope and purpose through coding. She told her children, “I know that this is probably going to seem really selfish... I really want to stay in prison and do this program. I feel like it’s really gonna help me overcome a lot of barriers job-wise.” Their support was unwavering.

After her release, Billie initially worked at Goodwill before landing her dream job as a help desk technician for the Indiana Pacers. Each day, as she pulls into Gainbridge Fieldhouse, she reflects, “I cannot believe I’m coming to work for this organization.” Her journey from incarceration to employment with her favorite NBA team exemplifies the transformative power of opportunity and determination .

And it’s not just about coding. It’s about identity. The old system stamps “inmate” on your chest and defines you by your worst day. This one asks: What can you build? What do you want to contribute? What if your past isn’t the final version of your story?

The results are undeniable. The national recidivism rate hovers around 60%. For Last Mile graduates? Just 4.6%. Nearly all of them find employment after release—some at places like Slack and Dropbox.

Chris and Beverly didn’t just break a precedent. They rewrote the logic of an entire system.

We talk a lot in tech about moving fast and breaking things. But what if the real disruption is moving deliberately and rebuilding something broken—line by line, life by life?

Because if a system was built to fail, maybe that’s the clearest call to start building something new.